Open Government at Legal Aid Ontario

Published: July 16, 2019

Promoting transparency and accountability in Ontario’s Justice System

1. Introduction

1.1 Why is LAO consulting on open government?

In recent years, the momentum for greater transparency and accountability in public institutions has accelerated. For example, the provincial government has identified open government as a key government-wide initiative. Premier Wynne has stated that:

We need to make information easier to find, understand and use, so that we can design services that deliver better results to the people of Ontario.

Part of this process will be the use of innovative models of public engagement, giving you a greater say on a range of items, including transit, regional economic development, and fiscal responsibility. We will also create a central space online where people can find information about government consultations, get engaged in that process, and express their ideas on government policy.

We must also unlock public data so that you can help us solve problems and find new ways of doing things. I believe that government data belongs to the people of Ontario and so we will make government data open by default, limiting access only to safeguard privacy, security and confidentiality.1

In October 2013, the Minister of Government Services established the Open Government Engagement Team to find ways for the Government of Ontario to be more open, transparent, and accountable. Their report, Open by Default,2 makes a series of recommendations that will help change the culture of government so that it becomes more receptive to public input and feedback, and more transparent with regards to sharing information and data.

The report also organizes “open government” initiatives into three distinct but related components:

-

Open Data — proactive publishing of data collected by government in free, accessible and machine-readable formats and encouraging its use by the public as well as within government;

-

Open Information — proactive release of information about the operation of government to improve transparency and accountability, and promote more informed and productive public debate; and,

-

Open Dialogue — proactive use of new methods to provide the public with a meaningful voice in planning and decision-making so government can better understand the public interest, capture novel ideas and partner on the development of policies, programs and services.

Ontario’s commitment to these initiatives took a significant step forward in November 2015 with the release of the Open Data Directive (ODD).3 The ODD takes effect on April 1, 2016 and will apply to all Ontario ministries and provincial agencies, including Legal Aid Ontario (LAO). It requires institutions to make data public and “open by default,” unless it is exempt for privacy, legal, confidentiality, security or commercially sensitive reasons. The directive will ensure that open data does not contain personal or confidential information.

LAO is releasing this consultation paper because it wants to promote Ontario’s open government framework in the justice system. By adopting the principles of open data, open information and open dialogue, LAO has an opportunity to integrate transparency into the fabric of the organization and to be the benchmark among Ontario’s justice institutions.

Achieving this benchmark is important. Open data helps LAO communicate the value of legal aid advocacy services to the province. Open information helps make policies and programs more transparent. And open dialogue facilitates greater public participation in LAO’s decision-making process. LAO believes the great potential of these open government principles for the justice system is the promotion of public awareness, greater public understanding, active public engagement, and the promotion of transparency and accountability in Ontario’s justice system.

1.2 What is LAO consulting on? What are the key questions?

This document sets the stage for a conversation about LAO’s existing open government commitments, and introduces the potential for greater open government initiatives at LAO and in the justice system. Achieving these goals is not without challenges. Public input is essential to understanding needs and opportunities, and to identify material of greatest interest and priority.

LAO has already made considerable investments in open government principles and initiatives. LAO believes that next steps should build on these existing efforts through stakeholder and public consultations, and by looking to new opportunities made possible by modern policies and technologies. This consultation document is therefore organized around the following three sections.

-

What are LAO’s current open government commitments?

LAO’s public website demonstrates an active and ongoing commitment to proactive disclosure of expense information and contracts, publication of key financial and service data, and reporting on the determination of freedom of information requests. LAO also regularly engages a wide array of stakeholders in consultations and advisory meetings and routinely publishes various reports on a quarterly and yearly basis.LAO is therefore interested in hearing about the following:

-

Is this information easily accessible? What is the best form of making this information available? Are there other approaches or formats that would be better?

-

What data or information should LAO publicly disclose that is not currently available?

-

How can LAO better promote open government for LAO services, governance, and operations?

-

-

What is LAO interested in doing to expand open government?

LAO intends to build on existing open government efforts and deepen its commitment to open government through a series of open data, open dialogue, and open information initiatives.LAO is therefore interested in hearing about the following:

-

What kinds of justice sector data sets are of public value, academic or scholarly interest, or would contribute to greater transparency and accountability?

-

Do disclosure techniques like aggregate data and anonymization adequately protect personal privacy in the justice sector? Do they maintain “privacy by obscurity”?

-

How can LAO continue to build on existing open dialogue and public engagement initiatives? What kinds of issues benefit from greater stakeholder and public participation?

-

Is it important to release raw data sets with supplemental information to ensure it is given appropriate context and not misinterpreted?

-

What kinds of initiatives should be given greatest priority?

Understanding “privacy by obscurity”

Openness and transparency are cornerstones of a fair justice system. Judicial hearings and court records are generally presumed to be open to public observation and scrutiny. But practically speaking these are often difficult to access: hearings have to be attended in person, and paper records have to be sought at a court house or archive. An extended discussion of how the electronic age intersects with this traditional “privacy by obscurity” can be found on pages 18-19.

-

-

What are the broader open government opportunities in the justice sector?

In addition to open government at LAO, this paper considers potential initiatives to promote open government objectives both for LAO-funded services and other actors in the justice system. For LAO and the justice system, promoting open government means having the potential to better communicate the social return on investment from legal aid services, elucidate issues of public concern like overrepresentation of accused with mental illnesses or who are First Nations, Metis and Inuit, and making justice sector data more widely to academic, policy, judicial, and government researchers. There are dozens of examples from other jurisdictions about these kinds of initiatives.

-

What kind of a balance should the justice sector continue to strike between openness and “privacy by obscurity”? What are some ways to strike this balance?

-

What is in it for the justice sector and participants to make information more widely available?

-

How can LAO promote proactive disclosure practices among community agencies and service providers funded by LAO? What kinds of regulatory or disciplinary information is valuable to the public interest and confidence?

-

How can other actors in the Ontario justice system improve transparency and open government?

LAO is therefore interested in hearing about the following:

1.3 How will LAO be consulting, and what are the expected outcomes?

An initial formal public consultation process will take place following the launch of this paper on a date to be announced in 2016. LAO will adopt several approaches to ensure broad and thorough consultation, including:

-

Written submissions. LAO invites organizations and individuals to provide written submissions at any time to opengovernment@lao.on.ca.

-

In-person group consultation sessions. LAO invites recommendations highlighting specific priority issues, and around which focus groups could be convened.

-

One-on-one consultation sessions with targeted organizations.

-

Live webcast consultation sessions with stakeholders and clients across the province.

Following the formal consultation period, LAO will publish a consultation report summarizing the feedback received from across the province and identifying next steps. Questions, submissions and suggestions can be also addressed directly to the following, in either English or French:

Marcus Pratt, Director of Policy & Strategic Research

Ryan Fritsch, Policy Counsel

Email: opengovernment@lao.on.ca

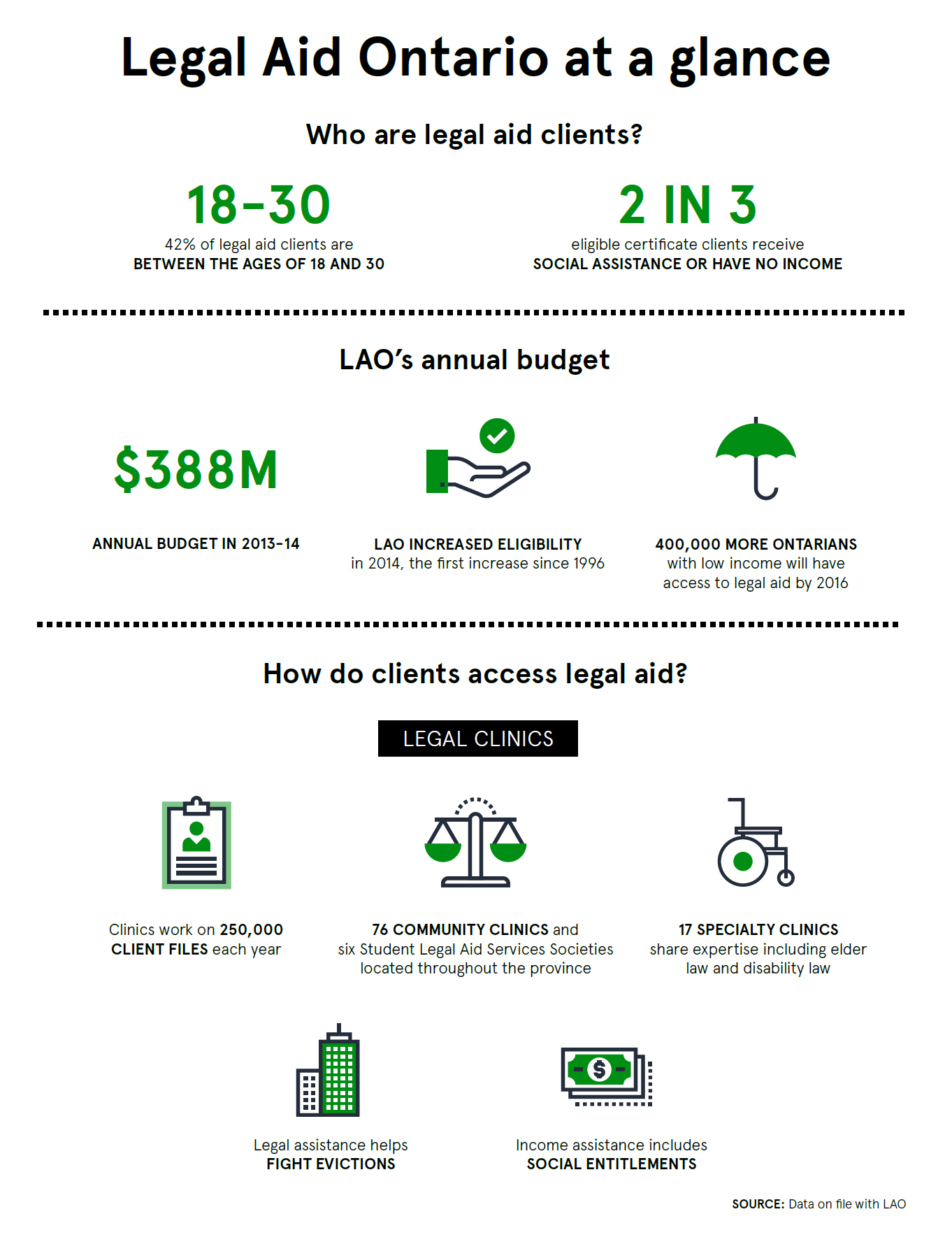

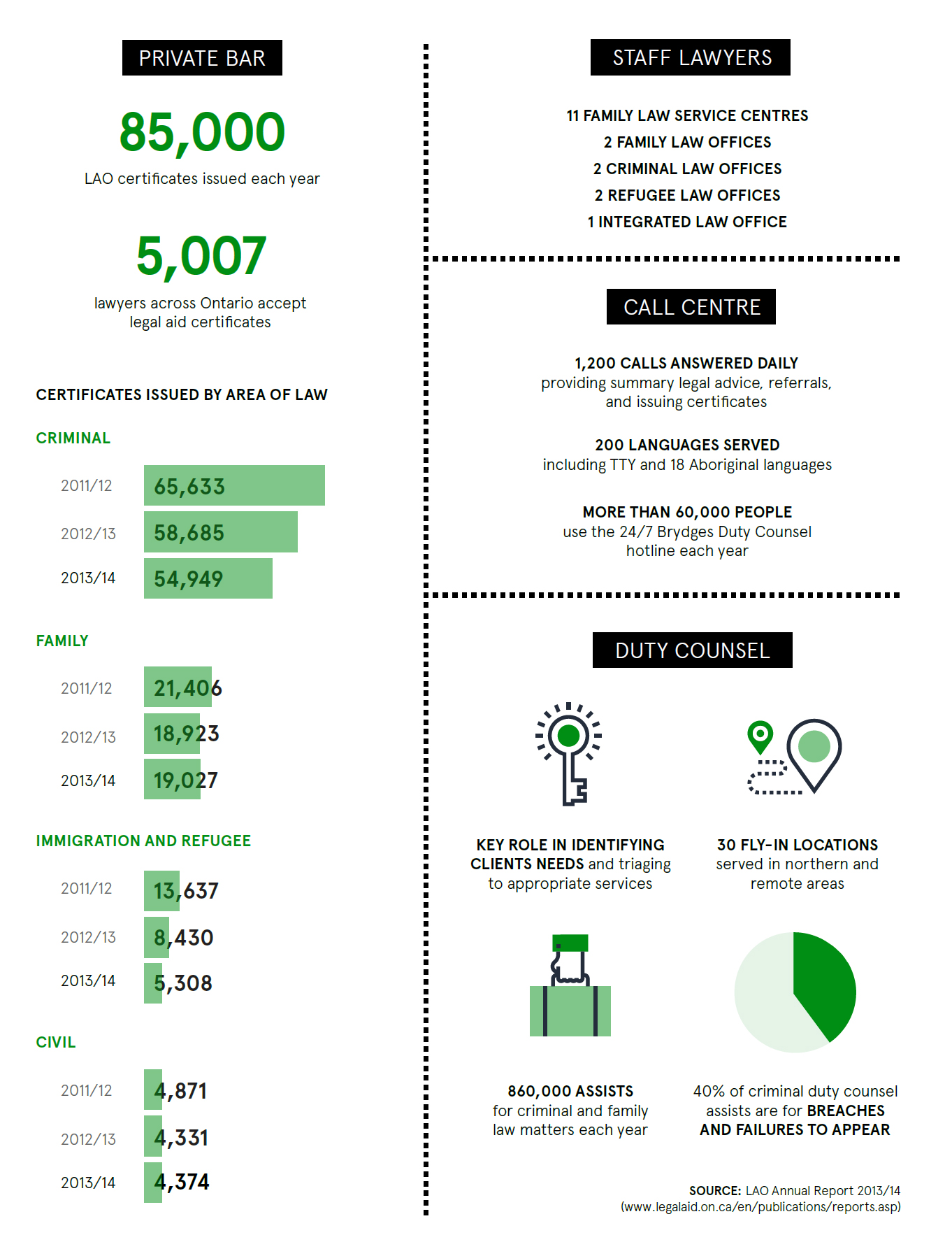

2. Legal Aid Ontario at a glance

3. What are LAO’s current commitments to open government

“Open government” broadly refers to accountability and transparency in publicly-funded institutions. These principles are understood as fundamental to modern public administration, and can improve governance and public accountability, build confidence in public institutions, and invite public, client, academic and stakeholder engagement.

Several jurisdictions, including the federal and Ontario provincial governments, have begun implementing a commonly accepted framework defining “open government.” As outlined in Ontario’s Open By Default report, this framework is comprised of three distinct but related concepts: open information, open dialog, and open data.

Open government may also be seen as an extension of existing accessibility and engagement policies and laws. Ontario legislation such as the French Language Services Act, 1986 and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 have made government services more accessible and available.4 LAO has adopted both, first launching a French Language Strategy in 2007 and establishing corporate-wide accessibility policies and procedures.5 A key commitment is to ensure the open government initiatives continue to ensure information and services are provided in both English and French, and in formats which are readily accessible.

LAO additionally believes that discussions about open government must include heightening public awareness of the special privacy and privilege requirements inherent to the justice sector. Many of these are defined by the Legal Aid Services Act (LASA) – the enabling statute that governs Legal Aid Ontario – and include the following:

-

Under s.89 of LASA, LAO has a positive obligation to protect the confidentiality of client information that it receives in the course of providing legal aid services to low-income Ontarians.

-

Section 89 also provides that LAO is bound by solicitor/client privilege with respect to information it collects about applicants for legal aid.

-

Under s. 90, all information received by LAO officials and employees in the course of providing legal aid services is prohibited from disclosure except as authorized by LAO. This provision is wider than the confidentiality provision of s.89, and encompasses more information than that about legal aid applicants.

LAO’s decision-making about the release of information is also subject to overview by the Information and Privacy Commissioner under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA). Open government initiatives, including the exceptions to being “open by default,”6 must work in concert with these kinds of obligations.

It is within these contexts that LAO has committed to its current open government initiatives, as outlined below.

3.1 Open Information – Current Examples at LAO

Open information includes proactively publishing FOIs, salary disclosures, expenses, contracts, and quarterly and annual organizational performance reports. Open information is generally released through reports, which include data that are easy to read and use.

At present, LAO proactively posts online:

-

Annual Report: LAO submits an annual report to our funder, the Ministry of the Attorney General, which includes an overview of programs and activities, a report on client services, and the annual financial statement.

-

Quarterly reports: these reports are issued on a quarterly basis and include updates on the organization’s financial position, client services, legal aid certificates, and lawyer payments.

-

Executive expenses: PDF copies of the quarterly expense reports for the LAO’s senior management, President and CEO and the Chair of the Board of Directors.

-

Contracts and expenses: PDF copies of contracts made between LAO and various vendors, sorted by fiscal year.

-

Service agreements: details of service agreements made between LAO and other organizations.

-

Public proceedings of the Board: these are posted throughout the year.

-

Data and Information requests: requests and responses for raw data or information.

Additional and detailed information in each of these categories is available online through LAO’s public website.7

LAO has also established a public website detailing FOI statistics.8 As with all government institutions, LAO has experienced a significant and accelerating increase in FOI requests in the last several years. A snapshot of FOI requests include the following:

-

From January 2000 to March 2015, LAO received 248 requests for access to information.

-

Approximately 30% of those requests were for access to a client’s own personal information; 77% were granted, 16% were partially granted, and 4% of requests had no responsive records.

-

About 36% of all requests received during that time period were by either third parties or by clients for third party information; about 20% were granted and approximately 14% were partially granted.

-

Approximately 34% of all requests for access to information received during that time period were for access to general information about LAO; approximately 55% were granted and nearly 22% were partially granted. 10% of requests were refused and 13% of requests had no responsive records.

-

A decision was rendered within 1 to 30 days for approximately 68% of requests for information between 2010 and 2014. Approximately 29% of decisions were rendered within 31 to 60 days.

-

-

Relatively few FOI requests were appealed to the Information and Privacy Commissioner.

-

20 appeals were filed between 2008 and 2014. Of these, 5 were resolved at mediation; 13 were closed or dismissed by the IPC; 1 was abandoned and 1 was pending.

-

To ensure access to information, LAO made it its general practice to not charge clients an application fee for requests for personal information pertaining to their own records.

3.2 Open Dialogue – Current Examples at LAO

Open dialogue is about the commitment to provide opportunities for LAO’s clients and stakeholders to have a voice in the policies, programs, and services LAO develops and delivers whenever and wherever possible.

In addition to proactive publication and FOI requests, LAO engages in extensive public consultation to improve public access and drive transparent decision making. In just the last year, for example, LAO has conducted:

-

16 biannual meetings of the Advisory Committees appointed to provide feedback directly to LAO’s Board of Directors.9

-

Dozens of meetings with lawyers’ organizations on issues as diverse as administrative irritants, alternative fee arrangements, family law expansion initiatives, test case initiatives, and new practice standards for refugee lawyers.

-

Extensive province-wide consultations on LAO’s Mental Health Strategy, Domestic Violence Strategy, Aboriginal Justice Strategy, and French Language Strategy, refugee reform initiatives, and clinic law consultations, among others. LAO’s recent Mental Health Strategy consultations, for example, included more than two dozen in-person group consultations sessions in communities across Ontario, release of a consultation paper receiving over 750 unique downloads, and receipt of over 65 formal written submissions from individuals and organizations.

In late 2015, LAO’s Board adopted an expanded disclosure policy to include publication of minutes from Board Advisory Committee meetings with external groups. This initiative invites the public to review the kinds of advice and issues LAO’s Board receives from their twice-annual meetings with a diverse group of individuals and stakeholders. Public versions of these documents will be translated and put on the website following formal approval of the minutes by the committees. Online posting of this material is set to commence with the Spring 2016 Committee meetings.

These are all initiatives which support open dialogue. LAO’s recent financial eligibility and client strategies have also engaged in robust and transparent provincial consultations. Stakeholders, clients, and service providers in fields outside of law have directly engaged with key policy and service issues, identifying areas of concern, providing input on priorities, and suggesting innumerable options and innovations.

Consulting Ontario about expanded access to justice

In October of 2014, the Government of Ontario announced $154M in funding for Legal Aid Ontario to expand financial eligibility and introduce new services to improve access to justice. Since January 2015, LAO has convened over 40 expansion consultation meetings, including almost 400 individuals and four dozen institutions and organizations in the process.

Improving lawyer accountability

LAO’s Refugee and Immigration Panel Services Department recently concluded public consultations on lawyer service quality. These consultations contributed directly to the creation of new refugee and immigration practice standards. All lawyers wishing to represent legally-aided clients with refugee and immigration matters are now required to demonstrate they meet the new practice standards by July 17, 2015. An additional appellate-level standard was also introduced to ensure appeal counsel are sufficiently experienced and expert.

3.3 Open Data – Current Examples at LAO

“Open data” is the broader effort to recognize data as a public asset, and more specifically as the practices and policies providing public access to a wide range of data and datasets. This includes familiar practices such as service data; objectively measured facts, figures and statistics; and the data that informs reporting and analysis in annual reports, business plans, and salary disclosure. Open data is the publishing of data that is accessible, meaningful, and easily understood. Open data is generally released in data sets; in other words, raw data that has been untouched, unfiltered, and not manipulated in any manner.

Notwithstanding these potential benefits, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that publishing data for its own sake is unlikely to be meaningful. Data must have a value to stakeholders before time and effort is invested in its preparation and release. Consideration should also be given to releasing data with the appropriate context provided, such as information about underlying policies that may be driving trends or outcomes, or by providing relevant comparisons.

3.4 Consultation questions on LAO’s current open government commitments

In light of these current and ongoing open government commitments, LAO is interested in public feedback about the following:

-

Is this information easily accessible? What is the best form of making this information available? Are there other approaches or formats that would be better?

-

What data or information should LAO publicly disclose that is not currently available?

-

How can LAO better promote open government for LAO services, governance, and operations?

4. What is LAO interested in doing to expand on open government?

LAO is currently reviewing opportunities for increased open government and open data initiatives beyond current efforts. LAO would like to hear from Ontarians about the kinds of information and approaches of greatest interest to them. Several open government options are under consideration.

4.1 Expanding open dialogue initiatives

Stakeholders and members of the public have suggested that open dialogue could be expanded through several practical efforts. For example, LAO could publish more consultation reports to: summarize feedback received through consultation initiatives; publicly report on the issues raised by stakeholders; and show how these issues informed LAO’s deliberation and decision-making process.

LAO is also reviewing confidentiality practices of the Board of Director’s Advisory Committees to make a wider array of meeting minutes public, and to facilitate greater public sharing of the information provided by LAO members of the advisory committees.

LAO has also conducted major client strategy consultations, such as the Mental Health Strategy, Aboriginal Justice Strategy and Domestic Violence Strategy. However, LAO believes there is greater opportunity to more routinely engage in –and report on–– consultations on public-facing policies, such as “change of solicitor” practices or procedures for legal appeals.

4.2 Expanding open data and open information initiatives

In addition to increased transparency in governance, many institutions are exploring ways in which data can drive greater transparency, accountability and innovation in the justice sector.

Ontario’s new Open Data Directive provides some guidance on how to identify and prioritize data and datasets for release. Among these, the topmost considerations are:

-

Public feedback: Data is considered of high interest or value if it is the subject of a high number of public website searches, related webpage usage (e.g., similar datasets or info), “freedom of information” (FOI) requests or email/correspondence requests

-

Transparency & accountability: Data that increases transparency and accountability, specifically data used to create legislation, regulation, policy or program and service evaluation, or data related to asset management, procurement contracts and audited financial information (e.g., Public Accounts) is considered high-value

-

Policy evaluation: Releasing data that is useful for internal and external stakeholders’ evaluation of the delivery of policy, programs or services can be considered high-value. However, usefulness requires timely frequent release in order to support effective evaluation.10

LAO is very interested in public feedback on the kinds of transparency, accountability and policy evaluation material that is of greatest interest and priority to Ontarians.

Some examples are given below of the kinds of initiatives which LAO could adopt as new ways to measure and report on the efficacy and outcome of justice services. Potential concepts could include:

-

Service level metrics, including monthly certificate statements, quarterly geographic and demographic snapshots, and duty counsel assists.

-

Quality of service metrics, including client satisfaction and experience data, transparent panel practice standards, and panel enforcement efforts.

-

Corporate accountability metrics, including a “financial health” report, disclosure of clinic expense reports and salaries over $100K, aggregated (non-identifiable and non-individual) billing data for private bar services, and clinic staffing activities and vacancies.

-

Development of new measures of value and social return on investment that provide a more sophisticated analysis of client needs and client outcomes, such as lasting resolution of legal issues, reduced criminal recidivism, successful results linked to social determinants of health like housing and income stability, and a clearer picture of the client service pathway across several different justice services.

-

Open data initiatives, including online access to the above information and raw datasets.

The power of open data

Open data can bring new perspectives to services and help answer critical questions. LAO often responds to requests from academics and other interested parties by providing data about LAO services and expenditures. Examples of this include service statistics about refugee law to support academic research, criminal costs and services to support research by the Criminal Lawyers Association, and information about lawyers to support academic research into barriers for women practicing criminal law. Making such data open and accessible to all interested parties will make it possible for others to investigate the kinds of forces shaping the legal marketplace, and create new approaches to expanding access to justice.

Many individuals and institutions are also exploring new kinds of electronic tools and infrastructure to make their activities more transparent and accessible. LAO could consider the same kinds of initiatives, such as:

-

A live, online “dashboard” showing up-to-the-moment service indicators including type of service, geographic area, type and location of general inquiries, and other such information. This would be similar to the recently launched Justice BC Dashboard.11

-

An online directory of administrative and management staff, similar to the Ontario Public Sector standards governing the Ontario Info-Go Service.12

-

Online hosting of interactive “legal health check-up” tools or “legal issue diagnosis” tools that can be used by service providers and the public to identify legal rights, legal issues, and legal aid service options.

-

Online publication of raw data sets and the results of their analysis by third parties.

-

Hosting and promoting legal apps built using raw data, and convening “legal hackathons”

-

Events in partnership with universities and technology groups.

-

Online publication of academic studies, social innovation lab events, and other organizations making use of legal aid and justice system data. This may include innovative measures of the justice system, such as how legal rights advocacy improves client outcomes in relation to social determinants of health, stability, and independence.

-

Online hosting of public legal education resources and live, interactive sessions with subject matter experts.

It is important to LAO that any material which can be posted online is valuable and useful to stakeholders. Like all government agencies, LAO makes online information available in both official languages and ensures formatting compliance with accessibility guidelines. Even documents of modest size can require several days of preparation for posting, including additional time where tables, charts or graphs are included. LAO is interested in hearing from the public about the kinds of information they would prioritize and are most interested in receiving.

4.3 Expanding Salary Disclosure

LAO is also weighing the merits and value of wider salary disclosure. At present, legal clinic salaries over $100,000 are not disclosed, unlike in the rest of Ontario’s public service sector. Similarly, private bar billings are not reported individually or in the aggregate (using non-identifiable and non-individual data). This might be compared to physician billings, which are individually disclosed in BC and Manitoba. This type of transparency makes the work of the justice system more visible to the public, clients, governments, funders and stakeholders.

However, care has to be taken to preserve privacy and to ensure that billings data represents a true picture of value, such as having to cover overhead, administrative costs, and some disbursements. LAO is interested in public feedback on how to strike the right balance between greater accountability, public confidence, and how the value of various legal aid services are measured and communicated.

4.4 Consultation questions on what LAO is interested in doing to expand open government

-

What kinds of justice sector data sets are of public value, academic or scholarly interest, or would contribute to greater transparency and accountability?

-

Do disclosure techniques like aggregate data and anonymization adequately protect personal privacy in the justice sector? Do they maintain “privacy by obscurity”?

-

How can LAO continue to build on existing open dialogue and public engagement initiatives? What kinds of issues benefit from greater stakeholder and public participation?

-

Is it important to release raw data sets with supplemental information to ensure it is given appropriate context and not misinterpreted?

-

What kinds of initiatives should be given greatest priority?

5. What are the broader opportunities in the justice sector?

In addition to open government at LAO, this paper considers potential initiatives to promote open government objectives both for LAO-funded services and other actors in the justice system. This broader focus stems from 1) LAO’s role as a major funder of public services, and 2) LAO’s statutory mandate to “advise the Attorney General on all aspects of legal aid services in Ontario, including any features of the justice system that affect or may affect the demand for or quality of legal aid services.”13

The need for open government is particularly important in the justice system and for independent, publicly-funded agencies such as LAO. Open Information through transparency and accountability are the necessary corollaries of independent decisionmaking. The justice system is also generally perceived as lagging other public services in the dissemination, gathering, sharing, and analysis of information and data.14

For LAO and the justice system, promoting open government means having the potential to:

-

better communicate the social return on investment from legal aid services, including important client outcomes for related to maintaining housing, accessing a stable income, resolving family law disputes, reducing criminal recidivism, and facilitating access to justice and equal rights for vulnerable clients including victims of domestic violence, persons with a mental health issue, and First Nations, Metis and Inuit;

-

improve decision-making transparency, public accountability, and public participation;

-

promote greater client, stakeholder and public understanding of justice system and legal aid priorities, plans, services, operations, and benefits;

-

facilitate innovation in policy, programming, and business modeling;

-

make the work of the justice system and LAO more visible to clients, the public, governments, funders, and stakeholders; and,

-

make data and information accessible to academic, policy, judicial, and government researchers.

There are literally dozens of examples across the world of efforts to increase openness and transparency within public institutions, including justice sector. Appendix A includes a list of some notable examples from other jurisdictions/sectors.

5.1 Striking the balance – open data and justice sector privacy

It is additionally and equally as important to balance transparency and open government with the right to privacy. Striking the right balance is particularly important in the justice system where sensitive client or other information is often protected by law or by what is sometimes called the “privacy by obscurity” of paper records and in-person hearings.15 It is also important to acknowledge the very real practical obstacles to greater transparency through open data, including database management and the limitations of anonymized data, aggregated data and other initiatives to protect privacy/confidentiality.

Many of these challenges are not explicitly dealt with in existing privacy laws. While there is some experience with these issues in the access to information context (where privacy interests are routinely balanced against the goals of transparency and accountability), this experience may not be well adapted to developments such as open data and proactive disclosure, nor may it be entirely suited to the dramatic technological changes that have affected our information environment.

Jennifer Stoddart, former Privacy Commissioner for Canada, said:

Put simply, this issue calls for what many say is the need to balance two values which are essential to democracy – privacy and access to information.

In other words, years ago, to retrieve this sensitive personal information, someone would have had to make the effort to go down to the court house and find the file. Today, that information is just a few key strokes away, anywhere, anytime.

Typically, when datasets are released publicly, certain information is removed to make the data anonymous. But when such data is analyzed in combination with other publicly available information, there is a risk of re-identification – a risk that is constantly increasing thanks to the trends I just mentioned. Privacy scholar Paul Ohm has detailed this challenge in a paper provocatively entitled “The Failure of Anonymization.” In it, he wrote that “data can either be useful or perfectly anonymous but never both.” 16

The issue is important, particularly when legally-public justice data, such as verdicts and sentences in criminal cases that are given out in open court and are a matter of public record, can be used to reveal personal information about a person other than the offender. In these situations, governments and institutions have struggled to find the right legal and administrative balance between privacy and openness.

With the ease of making such information electronically available and searchable, “privacy by obscurity” may be less influential as a means to balance the reasonable expectations of litigants with the judicial (and open government) principles of openness. In some ways, this shifts the question to “how should this information be made available? What is the best form for making this information public?”

5.2 Community legal clinics

Clinics provide important public services. LAO provides the overwhelming majority of funding for community legal clinics across Ontario. Clinics are also recipients of substantial new funding from LAO and the provincial government designed to promote financial eligibility expansion. For example, in 2013/14, LAO provided Ontario’s clinics with $67.8 million in core funding and $4.15 million in special project funding to upgrade aging information technology infrastructure. LAO also recently made available $3.3 million of new permanent funding to support financial eligibility expansion initiatives within the clinic system.

Clinics can support Ontario’s commitment to engage, collaborate, and innovate through increased transparency in several ways and are encouraged to use the Open Government initiative as a starting point to explore these opportunities.

At present, only charitable-status clinics have a requirement to report on this type of core funding distribution (to the Canada Revenue Agency). Through a transparency lens, support of the Open Government initiative would be to look at ways to make these reports more accessible and readily available to the public. Reporting on where core funding is flowing is fundamental to modern public administration, and can improve governance and public accountability.

In addition, the above discussion about salary disclosure considers how clinic salaries above $100,000 could be disclosed, further supporting open government accountability principles and aligning clinics with comparable practices, such salary disclosure for executives and physicians in community health centres.

Clinics also have an opportunity to embrace proactive public disclosure of funding, expenditures, services, and operations. Much of this information is already prepared reported to LAO: section 37 of the LASA states that a clinic funded by LAO will provide, upon request, audited financial statements for the funding period, a summary of the legal aid services provided by the clinic during the funding period, a summary of the complaints received by the clinic, and any other financial or other information relating to the operation of the clinic that LAO may request. A shift to proactive public disclosure of this information would be consistent with the Open Government initiative, and increase public confidence that resources are being used effectively.

5.3 Private bar services

LAO currently spends approximately $190 million in public dollars to private bar lawyers who provide legal aid services. Consistent with the above discussion, distribution of these private bar billings is not publicly disclosed, and may represent an opportunity to support Ontario’s commitment to achieving Open Government goals.

What are some other accountability measures are in place?

LAO routinely conducts random and targeted audits of private bar billings through the Audit and Compliance Unit. These audits look at several factors, ensuring that reported work is being completed and that billings comply with LAO’s policies.

Greater accountability and increased public trust in legal aid could also be bolstered by making LAO’s panel management process more transparent. Eligibility to provide legal aid certificate services requires private bar lawyers to satisfy and maintain quality service and practice standards. Lawyers who do not maintain the required practice standards may be removed from the panel. Public reporting of these removal decisions could increase public confidence that only highly qualified and capable lawyers are providing legal aid advocacy services. However, public safety and confidence must be balanced against the privacy interests of the lawyer; there are many reasons lawyers may be removed from the panel unrelated to poor quality of representation. The goal of increasing public confidence may well be served through anonymous reporting.

5.4 Consultation questions on broader open government opportunities in the justice sector

-

What kind of a balance should the justice sector continue to strike between openness and “privacy by obscurity”? What are some ways to strike this balance?

-

What is in it for the justice sector and participants to make information more widely available?

-

How can LAO promote proactive disclosure practices among community agencies and service providers funded by LAO? What kinds of regulatory or disciplinary information is valuable to the public interest and confidence?

-

How can other actors in the Ontario justice system improve transparency and open government?

6. Next Steps

LAO strongly encourages organizational stakeholders and individuals to consider the issues and options outlined in this paper and to make recommendations about how best to continue developing the open government initiative. The feedback collected during the consultation process will directly contribute to the development of multi-year plan to increase transparency, accountability, and participation in Ontario’s legal aid system.

After the close of the formal public consultation session, LAO will issue a consultation report for additional comment. LAO invites written comments at any time through opengovernment@lao.on.ca.

7. Summary of Consultation Questions

7.1 Consultation questions on LAO’s current open government commitments

-

Is this information easily accessible? What is the best form of making this information available? Are there other approaches or formats that would be better?

-

What data or information should LAO publicly disclose that is not currently available?

-

How can LAO better promote open government for LAO services, governance, and operations?

7.2 Consultation questions on what LAO is interested in doing to expand open government

-

What kinds of justice sector data sets are of public value, academic or scholarly interest, or would contribute to greater transparency and accountability?

-

Do disclosure techniques like aggregate data and anonymization adequately protect personal privacy in the justice sector? Do they maintain “privacy by obscurity”?

-

How can LAO continue to build on existing open dialogue and public engagement initiatives? What kinds of issues benefit from greater stakeholder and public participation?

-

Is it important to release raw data sets with supplemental information to ensure it is given appropriate context and not misinterpreted?

-

What kinds of initiatives should be given greatest priority?

7.3 Consultation questions on broader open government opportunities in the justice sector

-

What kind of a balance should the justice sector continue to strike between openness and “privacy by obscurity”? What are some ways to strike this balance?

-

What is in it for the justice sector and participants to make information more widely available?

-

How can LAO promote proactive disclosure practices among community agencies and service providers funded by LAO? What kinds of regulatory or disciplinary information is valuable to the public interest and confidence?

-

How can other actors in the Ontario justice system improve transparency and open government?

Appendix A: Examples of Justice Sector Open Government and Open Data Initiatives in Other Jurisdictions

A.1 Canada – British Columbia

British Columbia enacted the Justice Reform and Transparency Act, 2013 in March 2013. The Act is one part of the provincial government’s justice reform initiative aimed at making the justice system more efficient and effective. This legislation sets the framework for a well-functioning, transparent justice system that is strengthened by greater collaboration among justice leaders. The act has three purposes:

- to establish a new model to foster justice system collaboration and open data

- create new dialogue with the public about the system’s performance, and

- make reforms to the administration of the courts

The Act is accompanied by the BC government’s Justice Data Dashboard Initiative, available at https://justicebcdashboard.bimeapp.com/players/beta/jbc. The dashboard includes extensive information from the courts and corrections, including service data like average case length, number of cases heard and applications filed. The online tools enable users to filter content according to geography, date ranges, case type, type of court, etc.

The Queen’s Printer in BC has also partnered with the Ministry of Justice and Law Clerk of the Legislative Assembly to create QP LegalEze at http://www.qplegaleze.ca/default.htm. The site increases access to legislative materials for citizens of British Columbia and is made freely available in all Public Library Branches and BC Courthouse Libraries, with payment options for custom content sites and licensing.

Another initiative out of BC is Knomos.ca, “an interactive web app leveraging data visualization and deep machine learning to bridge the legal knowledge gap for everyone… restructuring the law in a more intuitive and usable way if we weren’t limited to words on a page.”

A.2 Germany

The Openlaws platform helps lawyers to do their work better and faster by aggregating EU legislations and case law. For citizens, it is an information hub on laws. Users can create personalized portfolios where they highlight or summarize important parts of the legal case for a group or for the public: https://www.openlaws.com

A.3 Argentina

The Transparent Contests initiative monitors and promotes citizen participation in the selection process of judges in Argentina. The initiative’s goal was to ensure that judges are non-partisan. The initiative put all data related to the competition for appointments online (including interviews) and applied big data analysis and crowdsourcing tools to identify political interference. It found that some appointments were affected by discretion and political interests. In 2014, when the Judiciary Council of the City of Buenos Aires held competitions for positions for magistrates, prosecutors, and defenders, it questioned the appointment of one of the magistrates due to poor performance of the magistrate during the competition which results in the State Legislature rejecting the appointment: http://acij.org.ar/acij/2012/en/news/creating-conditions-for-an-independentjudiciary/

A.4 Netherlands

The Dutch Legal Aid Board provides an online dispute resolution platform for divorces. All costs are fixed and transparent with reimbursement provided by the legal aid board to qualifying low-income participants: http://rechtwijzer.nl/

A.5 Cambodia

The Trial Monitoring Project at the Cambodian Center for Human Rights monitors trials in Cambodia to assess their adherence to international and Cambodian fair trial standard. The data is publicly reported, analyzed, and used towards substantive legal and judicial reform at all levels of the domestic court system. Trial monitors are used at each criminal trial to obtain quantitative and qualitative data based on a specific checklist. Its goal is to improve the procedures and practices of courts in Cambodia.

To date, it has monitored 1,722 trials in Phnom Penh Court of First Instance, 505 trials in the Kandal Provincial Court, 252 trials in the Banteay Meanchey Provincial Court, 65 trials in the Ratanakiri Provincial Court, and 14 other trials related to human trafficking and high profile cases in the Courts of First Instance throughout Cambodia: http://www.cchrcambodia.org/index old.php?url=project page/project page.php&p=project profile.php&id=3&pro=tmp&lang=eng

A.6 United States – Louisiana

The New Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office uses software to track criminal diversion clients to monitor and report on treatment and compliance. Identifiable and personal information relating to the diversion candidate is kept private. However, the Office publishes open data that correlates the characteristics of the diversion candidate and their case to the various support and treatment programs used, and then to the outcome or ongoing status of the diversion. This data is used to better identify and tailor diversion options for subsequent candidates, and thus to lower the rate of recidivism and improve candidate outcomes: http://www.courtinnovation.org/research/informationtechnology-social-services-tracking-clients-treatment-and-compliance

A.7 United States – California

The California Department of Justice transparency initiative has created an online dashboard with information and graphs related to arrests rates, death in custody & arrest-related deaths, and law enforcement officers killed or assaulted: http://openjustice.doj.ca.gov.

ZoningCheck is an open government legal web app that allows a business owners to quickly find the laws, regulations and ordinances that apply to their business: http://zoningcheck.us.

A.8 United States – New York

Campus Crime provides data on all sexual assault and violent crimes reported on all NY State college campuses: http://campuscrime.ny.gov

NYPD App lets users browse a “wanted gallery,” submit tips, view crime videos and crime stats, and see precinct boundaries to help preserve peace, reduce fear, provide safer environment, and enforce laws: https://developer.cityofnewyork.us/app/nypd

A.9 United States – Federal

The US Supreme Court Oyez Project provides a public database of all major constitutional cases heard by the US Supreme Court, including multimedia resources such as free digital audio of oral arguments. Also includes summaries of decisions, and state and appellate court documents: https://www.oyez.org

A.10 United States – Illinois

The Open Gov for the Rest of Us campaign engages low-income neighborhoods to connect more residents to the internet, promote the use of open government tools, and develop neighborhood-driven requests for new data sets. It looks to provide tools to access around issues important to those neighborhoods such as housing and education: http://opengov.newschallenge.org/open/open-government/submission/opengov-for-the-rest-of-us-/

A.11 United Kingdom

Check That Bike! is a search engine using open data and crowdsourcing to help UK cyclists avoid buying stolen second-hand bikes and to make those bikes a lot harder to sell, cataloging over 536,000 bikes stolen every year. It accesses all open data sources carrying information on stolen bikes in addition to information directly from police sources across the country: https://stolen-bikes.co.uk

TotalCarCheck provides vehicle history checks for £1.89 by using vehicle related data from the DVLA bulk data set and stolen vehicle data set from UK government’s data: https://totalcarcheck.co.uk

A.12 India

The M-Governance System is an integrated mobile application that aggregates all of the services and departments under the Government of Kerala – 90 departments and 150+ services. Allows for users to select service and learn more about service or submit a query related to the specific service and department. The public can lodge complaints such as child labor, accidents in real time, and track the status of their files: http://goo.gl/Jv7f8

Footnotes

Footnotes for 1. Introduction:

-

Premier Kathleen Wynne, “Let’s open up government to new possibilities” (October 21, 2013), online: http://www.ontario.ca/page/lets-open-government-new-possibilities.

Back to report -

Additional information, including the Open by Default report, is available on the Open Government Ontario website: https://www.ontario.ca/page/open-government. Ontario’s tripartite framework for “open government” is the same as that for the federal government. For more information see Canada’s Action Plan on Open Government 2014-2016 (2014), online: http://open.canada.ca/en/content/canadas-actionplan-open-government-2014-16#ch4-1.

Back to report -

“Ontario making Data Open by Default” (November 27, 2015), online: http://www.news.ontario.ca/tbs/en/2015/11/ontario-making-data-open-by-default.html

Back to report

Footnores for 3. What are LAO’s current commitments to open government?

-

The Office of Francophone Affairs provides programs and comprehensive information on Ontario’s efforts to be more accessible in both English and French: http://www.ofa.gov.on.ca/en/flsa.html.

Back to report -

For further information, please see LAO’s French Language Services page (http://www.legalaid.on.ca/en/about/frenchlanguageservices.asp) and the Accessible Services page (http://www.legalaid.on.ca/en/accessibility.asp).

Back to report -

The Open Data Directorate makes clear that in addition to any other statutory requirements or limitations, data is “open by default,” unless it is exempt for privacy, legal, confidentiality, security or commercially sensitive reasons, online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-open-data-directive

Back to report -

LAO, “Proactive Disclosure”, online: http://www.legalaid.on.ca/en/publications/disclosure.asp

Back to report -

LAO, “Overview of Access to Information Requests”, online: http://www.legalaid.on.ca/en/publications/inforequests.asp

Back to report -

There are currently 93 members of the public appointed to one of eight Advisory Committees. These committees represent each of LAO’s major service areas including criminal law; refugee & immigration law; family law; mental health law; Aboriginal law; French Language Services; prison law; and clinic law

Back to report

Footnotes for 4. What is LAO interested in doing to expand on open government?

-

Additional criteria are provided in the Treasury Board Secretariat, “Open Data Guidebook” (November 2015) at 7-8.

Back to report -

In 2013, the government of British Columbia passed the Justice Reform and Transparency Act, 2013. The “Justice BC Dashboard” is one early example of making more information publically available: https://justicebcdashboard.bimeapp.com/dashboard/adult

Back to report -

INFO-GO, the Government of Ontario Employee and Organization Directory: http://www.infogo.gov.on.ca/infogo/

Back to report

Footnotes for 5. What are the broader opportunities in the justice sector?

-

LASA s. 4(f).

Back to report -

See for example the concerns of the Auditor General, “Section 4.07, Court Services” (2010 Annual Report); “Section 3.07, Court Services” (2008 Annual Report); “Section 4.12, Youth Justice Services Program” (2014 Annual Report); “Section 3.02, Criminal Prosecutions” (2012 Annual Report); all available online: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/reports justice en.htm

Back to report -

Ontario’s Information and Privacy Commissioner helpfully addresses similar challenges in the municipal context. See Transparency, Privacy and the Internet: Municipal Balancing Acts, online: https://www.ipc.on.ca/english/Resources/Discussion-Papers/Discussion-Papers-Summary/?id=1530.

Back to report -

Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Open Government and the need to balance institutional transparency with individual privacy,” https://www.priv.gc.ca/media/sp-d/2012/sp-d 20121001 e.asp

Back to report